Introduction

DNA repair is an essential physiological mechanism for maintaining genomic integrity in nucleated cells. The DNA damage response (DDR) pathway has evolved

to be a complex, sensitive, highly integrated and interconnected pathway which can trigger a variety of cellular responses including DNA repair, cell cycle

arrest and apoptosis [

It is notable that heterozygous carriers of ATM mutation are relatively common amongst the general population, with estimates varying between 1.4

% and 2.2 %, and as high as 12.5 % in populations with a marked founder effect [

The ATM gene is extremely large - the full genomic region spans 150 Kb and consists of 66 exons [

The ATM gene encodes a Serine/Threonine protein kinase belonging to the PhosphatidyInositol 3 K

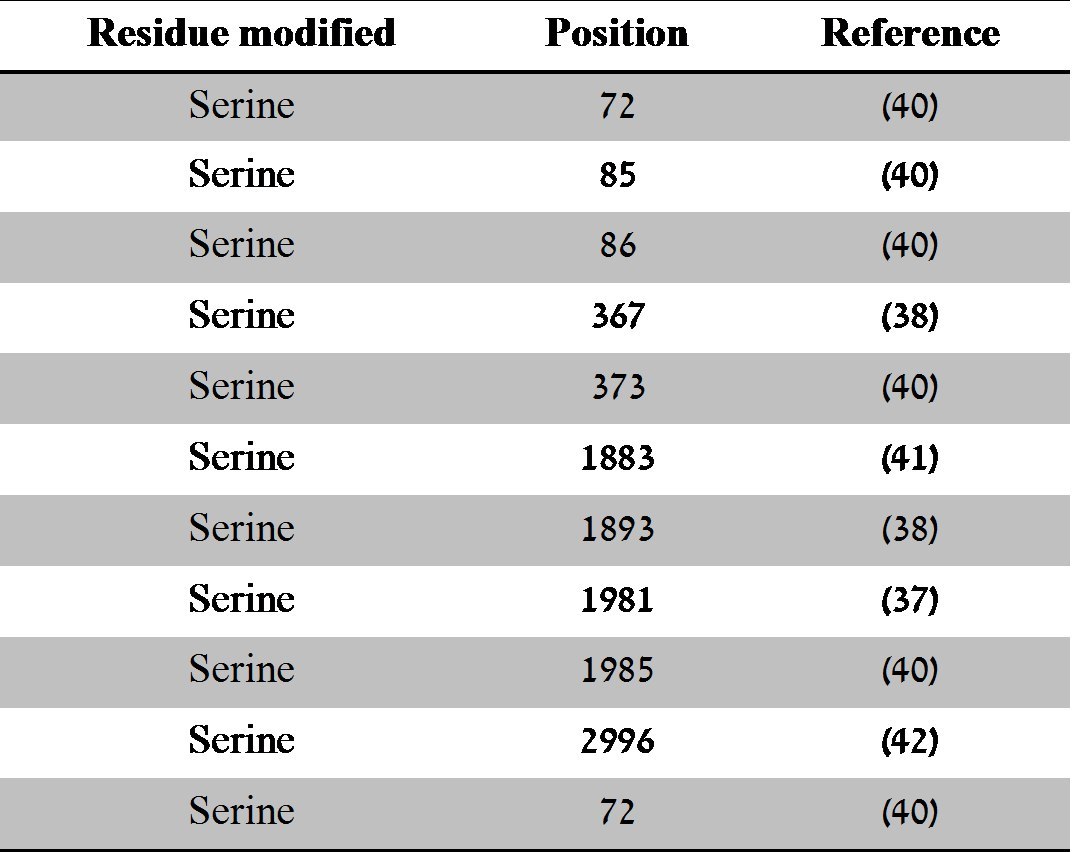

inase like Kinase (PIKK) super family. The ATM protein is a ~350kD nuclear protein comprised of 3056 amino acids [

However, of those listed, only the autophosphorylation sites at Serine 367, 1893 and 1981 have been fully characterised and play a role in ATM activation

[

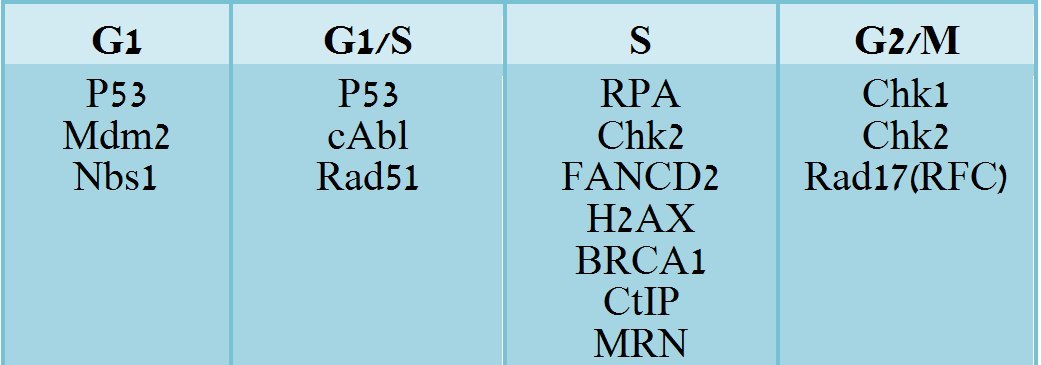

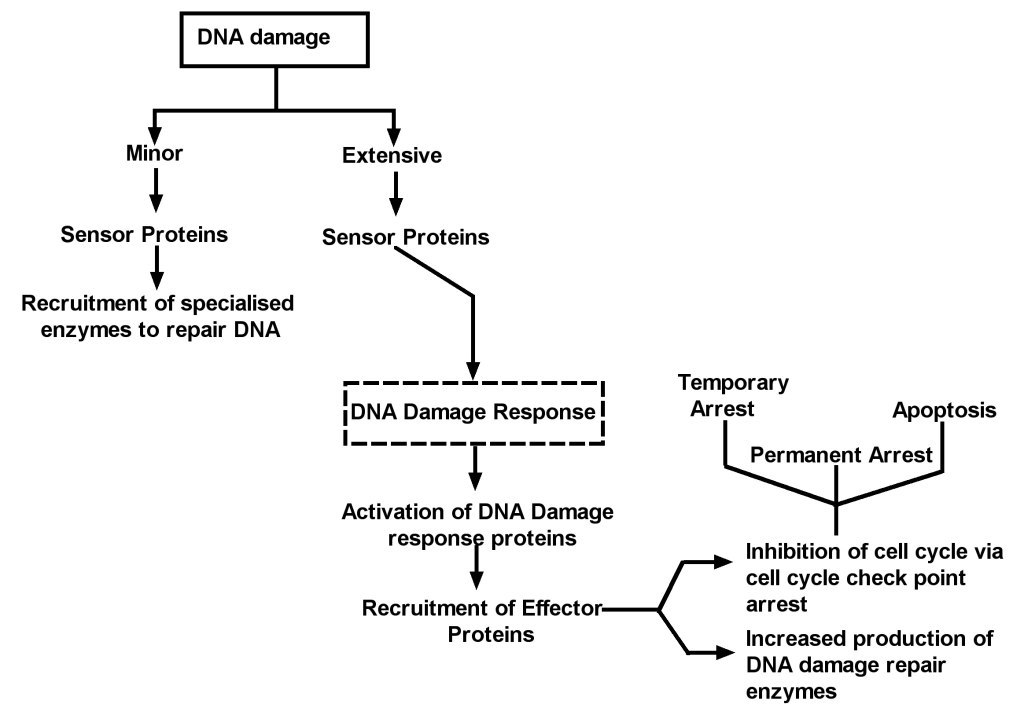

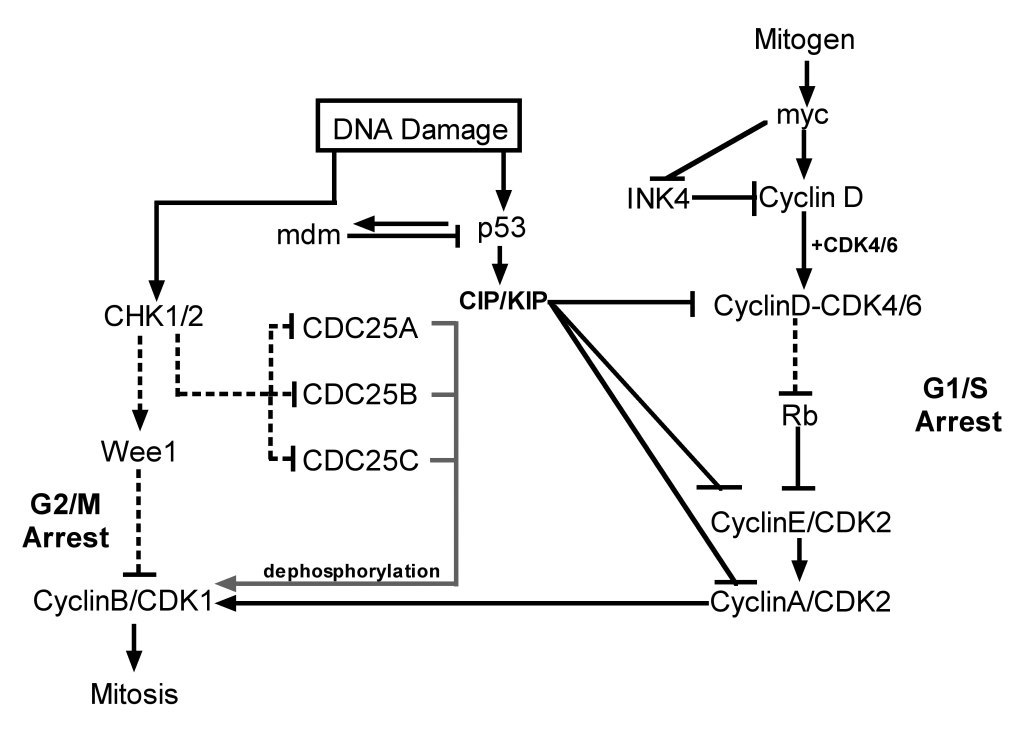

This functional link between the two pathways is very specific and tightly regulated at multiple levels. A simplified version of this pathway is shown in

Figure 1. DNA damage activates sensor proteins and transducers that recognize, relay and amplify the damage signal following genotoxic insult, and triggers

different cellular responses depending on the level of DNA damage. ATM also has a critical role in homologous repair during normal meiotic recombination

events [

Several early studies reported no quantitative changes in the expression levels and localisation of ATM throughout the cell cycle and upon DNA damage [

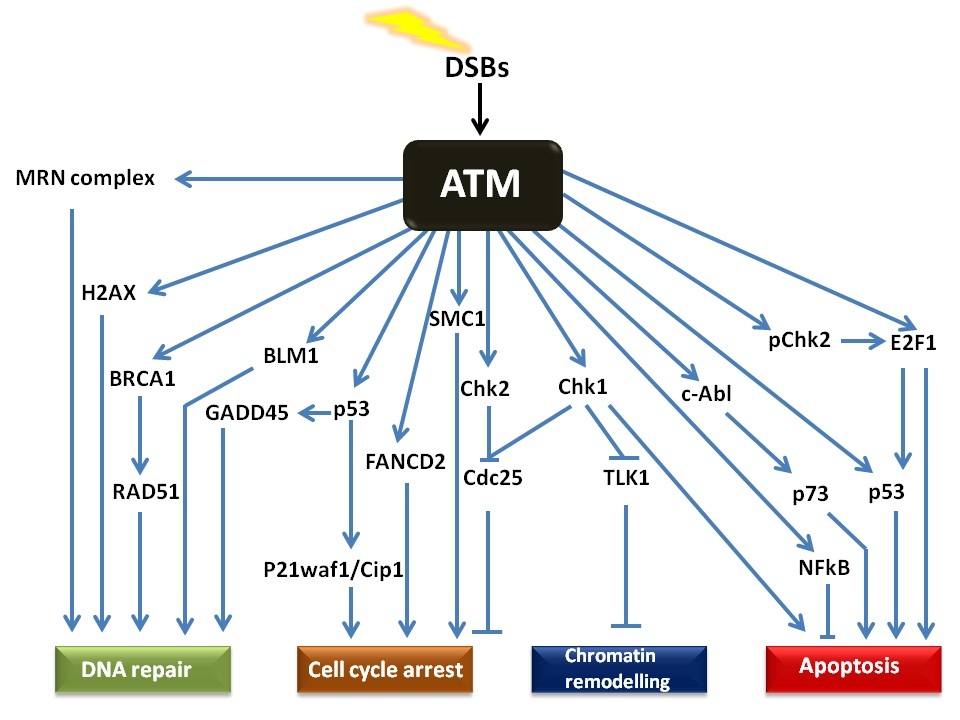

The ATM signalling pathway during DDR

The ATM signalling pathway is triggered after double stranded DNA damage and provides a robust and very sensitive detection mechanism which generates

responses that can cause cell cycle arrest, initiate DNA repair or induce apoptosis. The numerous substrates involved in the ATM signalling network are

illustrated in Figure 2. There is considerable cross-talk between the different ATM substrates and several of them provide functions in more than one

cellular response, which ensures a tightly co-ordinated and regulated cellular response. Following DNA damage, a variant form of histone, called H2AX,

previously buried within the chromatin microenvironment, becomes exposed due to changes in the higher order of chromatin structure. This is caused by

relaxation and unwinding of the local DNA supercoil due to the DNA breaks and recruitment of RAD51, exerting local topological changes. The phosphorylation

of H2AX on Serine 139 (referred to as γH2AX) by ATM represents one of the earliest events in the DDR and acts as a docking site for a variety of other

proteins involved in the DDR [

The MRE11 subunit of the complex has double strand exonuclease activity which excises the damaged DNA to allow for synthesis of a corrected strand. The

RAD50 protein has ATPase activity which along with RAD51, 52 and 54, is thought to be involved in holding the two broken DNA ends together and also

facilitate searches for homology in order to initiate recombination. NBS1 plays an important role of recruiting the MRN complex to the damaged site,

binding to the γH2AX and also facilitating the binding of ATM to the complex and its subsequent autophosphorylation and activation [

ATM deficient cells are unable to detect the levels of DNA damage which would otherwise result in activation of the DNA repair machinery, leading to sustained

genomic damage. Owing to the role of ATM in cell cycle arrest, ATM-deficient cells cannot induce checkpoint arrest following DNA damage, resulting in

replication of damaged DNA and propagation of errors until the burden of damage becomes too severe for the genome and the cell is directed to a suicide

route by an alternative, P53-independent mechanism [

The ATM signalling pathway during DDRTargeting ATM signalling pathway as an anticancer strategy

Decades of research efforts attempting to elucidate the DNA damage response pathways have added significant knowledge to our understanding of the mechanisms comprising DNA damage and repair signalling. These mechanisms involve sensing the DNA damage, generating a repair signal and amplification of the generated signal to elicit either a repair response, permanent arrest of the cell cycle, or apoptosis. Researchers have identified that cellular sensitivity to genotoxic agents in terms of cancer therapy can be achieved by modulating the function of key proteins involved in the above mentioned processes.

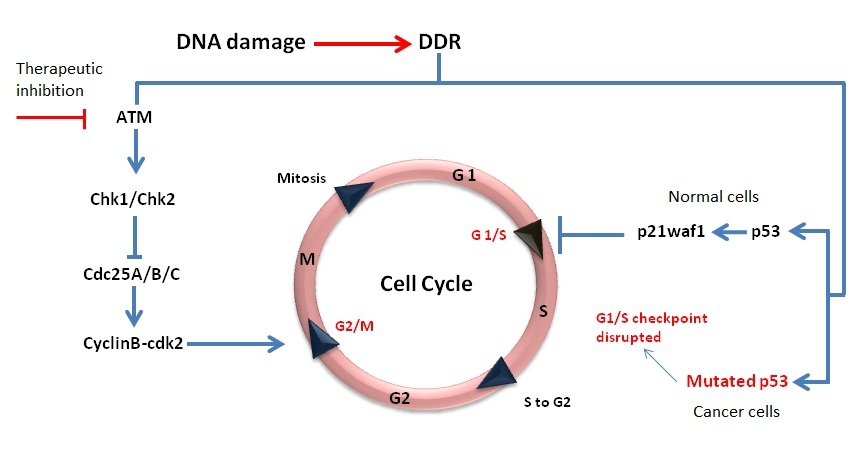

A key consideration in developing strategies for cancer therapy is to ensure the specificity of the cytotoxic action towards cancer cells as compared with their normal counterparts. This degree of specificity in terms of cellular response is theoretically achievable through identifying vital differences between normal and cancer cells and then basing the therapeutic approach on exploiting those differences.

Most, if not all cancer cells have mutations in genes affecting the cell cycle and DNA repair; these aberrations in vital cellular functions usually

enhance their survival potential under stress, handicap their ability to sense the DNA damage and result in a failure to arrest the cell cycle to

facilitate repair, leading to uncontrolled growth. However these abnormalities within cancer cells allow them to be distinguished from the surrounding

normal cells and this can be exploited to achieve targeted cellular sensitivity. More than 50% of all cancers have P53 mutations [

inhibition in P53 mutated cell lines (representing the majority of cancer cells) would theoretically cause more cytotoxicity after the same level of

genotoxic insult as compared to cells carrying wild type P53 (normal cells). The working principle of this strategy is illustrated in Figure 4. Another

potential substrate of ATM which could constitute a potential anticancer target is NF-B, a transcription factor that is activated as part of the stress

response and induces the transcription of genes that promote survival. In cancer cells, elevated or deregulated NF-B activation is commonly found.

Inhibition of ATM activity could prevent NF-kB-mediated cell survival and lead to NF-kB dependent sensitisation of such cells to IR triggering apoptosis

[

The concept of ATM inhibition-based anticancer therapeutic approach appears quite straightforward; nevertheless there are a number of challenges to

overcome. Theoretically, inhibition of ATM function would disable the DDR mediated cell cycle arrest, DNA repair and apoptotic pathways, but there are

other protein kinases sharing overlapping functions with ATM, such as DNA-PK and ATR. Thus, it may be necessary to inhibit all essential DDR kinases.

However, a less selective inhibitor may be more cytotoxic in normal cells. Secondly, ATM itself can induce apoptosis via P53 dependent and independent

pathways [

In our own studies, we have determined the consequence of ATM inhibition on cell survival after subjecting a normal breast epithelial cell line, MCF10A and a breast cancer cell line, MCF7 to different levels of double stranded DNA damage. Time course, and dose response experiments were conducted with the DNA damaging agent, Doxorubicin (Dox) in the presence or absence of the small molecule ATM inhibitor KU55933 (KU), and the extent of cell death was analysed using the Neutral red (NR) uptake assay (Supplementary fig. 1 A-D).

Time series treatment of 0.5μM Dox with and without ATM inhibition revealed different outcomes on cellular sensitivity towards genotoxicity and indicated context

dependent dual roles of ATM in the following way: Dox treatment alone resulted in decreasing NR uptake indicating cell death to varying degrees depending upon time of treatment and starting at the first time point in both cell lines. While MCF7 cell line was more sensitive to Dox at early time points of treatment with 50% cell death reaching at 12hr of Dox treatment (Supplementary fig. 1B), MCF10A was less sensitive with 50% cell death at 20hr of treatment (Supplementary fig.1 A). However, at a final time point of 24 hr Dox treatment, we observed comparable cell deaths between the two cell lines tested. Interestingly, addition of 10μM ATM inhibitor (KU) along with Dox resulted in higher apoptosis (hence sensitisation to the genotoxic agent) only at earlier time points of 2, 4, 8 and 12 hr of treatments as compared to Dox alone in both cell lines. Furthering the treatment regime contrastingly resulted in a lower cell death with the addition of ATM inhibitor than without, at 16, 20 and 24 hr time points (Supplementary figures 1A & 1B). Hence, it is indicated that at earlier time points, ATM kinase may mainly perform a cytoprotective function by triggering cell cycle arrest and DNA repair pathways as it ensured greater cell survival until 12 hr time point, as compared to that in ATM inhibited state. On the other hand, at a greater extent of DNA damage caused by longer genotoxic treatment beyond 12 hr, its function may have switched towards apoptosis, as there was higher cell death in functional ATM state than in inhibited state.

Dose dependent treatment of Dox ranging from 0.1 to 7μM with and without ATM inhibition similarly suggested a cytoprotective function of ATM at lower (0.1-0.25μM), while a role in apoptosis at higher (≥0.5μM) Dox levels in both MCF10A and MCF7 cell lines in the following way: Addition of KU with 0.1 and 0.25μM Dox resulted in greater sensitivity towards the genotoxic agent, and hence greater cell death in both cell lines as compared to Dox treatment alone. Increasing the dosage to and above 0.5μM Dox showed reduced cell death in ATM inhibited state than ATM active state. For example, when ATM was inhibited, 50% cell death occurred at a relatively higher concentration of 5μM Dox, as compared to 1μM in ATM active state (Supplementary fig. 2A).

Taken together, this data clearly demonstrates the different consequences of inhibiting ATM depending on the duration of treatment and dose of Dox used in

the experiments. While these results are preliminary, they could have an impact on how DDR modulating drugs could be employed in the clinic. For example,

in normal clinical practice, the physiologically achievable Dox concentration is maintained at approximately 100nM for up to 96hr by continuous infusion of

the drug [

Inhibition of ATM activity: Research strategies employed

Since ATM operates at the core of a signalling network that governs cell fate decision, manipulation of ATM function has become of increasing interest as a potential anticancer drug target. Theoretically, the attenuation of the DDR pathway should handicap the cellular machinery responsible for repairing damaged DNA, sensitise cancer cells to genotoxic insults and promote cell death after genotoxic treatments as illustrated in previous sections. This sensitisation of cancer cells could facilitate the use of reduced treatment regimens, which are less cytotoxic to normal cells but would still be sufficient to kill the cancer cells and achieve the desired efficacy. Such an approach would diminish the detrimental side effects of the drug on normal tissues and importantly has been demonstrated at the cellular level as well as in in vivo studies. Hence, one important therapeutic strategy is the identification of inhibitors of PIKK super family of kinases central to the decision making process of cell fate after genotoxic intervention. The discovery and characterization of these inhibitors has not only helped to elucidate the function of the relevant proteins but also to identify the most therapeutically relevant targets.

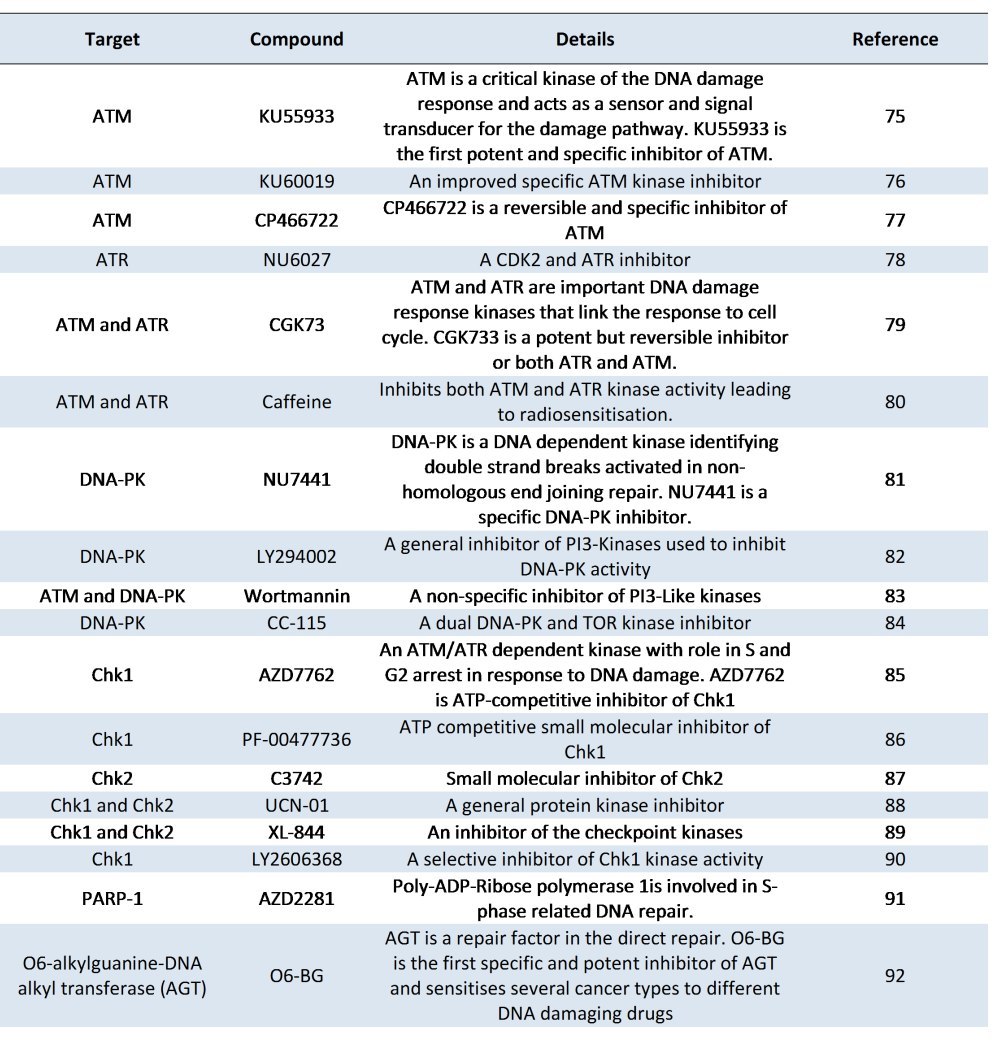

Table 3 is a list of recent inhibitors whose targets lie within the DNA damage response pathway. It is noteworthy that many of those listed in the table are either currently in clinical trials or have been in clinical trials. For example the Chk1 inhibitors AZD7762 and PF-00477736, and the broader spectrum Chk1 and Chk2 inhibitors UCN-01 and XL-844 as well as the PARP-1 inhibitor AZD2281 have completed clinical trials whilst the DNA-PK inhibitor, CC-115, the alkyl guanine transferase inhibitor, O6 BG, and a specific Chk1 inhibitor, LY2606368, are currently recruiting patients for clinical trials. In terms of exploiting the DNA damage response pathway for therapeutic intervention, the inhibitors of Poly ADP ribose polymerases have made the greatest progress and many novel drugs targeting

these enzymes are already in clinical trials [

There are several reports that demonstrate increased cellular sensitivity towards genotoxic agents by way of modulating the ATM signalling pathway through

inhibition of ATM kinase specifically. Upon DNA damage for example after treatments with chemotherapeutic agents or radiotherapy, some tumours undergo a

premature senescence also called stress-induced senescence. Although this permanent arrest of tumour cells is beneficial and prevents tumour metastasis,

such senescent tumour cells resist apoptosis and may re-enter the cell cycle [

Morgan SE et al [

Inhibition of ATM expression, via ATM antisense RNA or siRNA mediated gene silencing, is another strategy adopted by several researchers. Guha C et al [

Collis GC et al [

Recently, Neijenhuis S et al [

Truman JP et al [

In another study, Gueven N et al. [

A-T cells, which are highly chemo- and radio-sensitive have disrupted NFkB expression. Exploitation of the link between ATM and NFkB pathway regulation

(Fig. 2) is an interesting anticancer target and experiments have been successful using either a dominant negative form of the NFkB inhibitor, I Kappa B

alpha or inhibitors of ATM to disrupt the NFkB pathway in achieving chemosensitization and apoptosis of cancer cells [

The body of data described here has compelled many pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies to fund projects in this area, and the large number of DDR inhibitors currently being studied in clinical trials serves to illustrate the significance of this strategy in ongoing efforts to combat cancer.

New perspectives: Role of systems biology in the development and use of ATM inhibitors for anticancer treatment

A prerequisite of a molecularly targeted anticancer approach is a detailed understanding of the underlying molecular mechanisms contributing to tumour

development. Elucidation of these mechanisms would facilitate a better understanding of cancer biology, but would also provide for the identification of

potential drug targets that would also afford cancer selectivity. The latter, as mentioned before, is based on characterising differences between normal

and cancer cells. These differences are not only limited to DDR signalling pathways, but may also involve adaptive trafficking mechanisms, alteration in

cell surface receptors, differential microRNA expression levels and changes in both the types and extents of molecular interactions governing key processes

in a cell, all of which may influence drug efficacy. Additionally, a thorough understanding of the extracellular microenvironment, proliferation, growth

and stress signals, serum levels and of the phase of the cell cycle are vital before a successful anticancer approach could be actualised. Owing to a

central role of ATM in performing multiple functions after genotoxic insults, it is becoming clear that targeting the ATM signalling pathway may sensitise

cancer cells to the genotoxic agents used in cancer therapy. However, recent reports have identified greater complexity in terms of ATM function and

regulation [

We believe that this complexity in determining the absolute effects of manipulation of ATM activity could be best addressed by employing a systems biology

approach to the problem, involving mathematical modelling [

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor John Palfreyman and Dr Sheelagh Frame for the helpful comments and editing the paper. This research was supported by the Northwood charitable trust and grant No. DO02-69 at the Ministry of Education, Youth and Science of the Republic of Bulgaria.

References

- Kastan MB, Bartek, J. Cell cycle checkpoints and cancer. Nature 2004; 432: 316-323

Reference Link - Perlman S, Becker-Catania S, Gatti RA. Ataxia-telangiectasia: diagnosis and treatment. Semin Pediatr Neurol 2003; 10(3): 173-82.

Reference Link - Gilad S, Chessa L, Khosravi R, Russell P, Galanty Y, Piane M, et al. Genotype-phenotype relationships in ataxia-telangiectasia and variants. Am J Hum Genet 1998; 62(3): 551-61.

Reference Link - Gatti RA, Swift M. Ataxia-telangiectasia: Genetics, Neuropathology, and Immunology of a Degenerative Disease of Childhood. New York: Alan R. Liss 1985.

- Gilad S, Bar-Shira A, Harnik R, Shkedy D, Ziv Y, Khosravi R et al. Ataxia-telangiectasia: founder effect among North African Jews. Hum Mol Genet 1996; 5(12): 2033-7.

Reference Link - McKinnon PJ. Ataxia-telangiectasia: an inherited disorder of ionizing-radiation sensitivity in man. Hum Genet 1987; 75(3): 197-208.

Reference Link - Reed WB, Epstein WL, Boder E, Sedgwick R. Cutaneous manifestations of ataxia-telangiectasia. JAMA 1966; 195(9): 746-53.

Reference Link - Boultwood J. Ataxia telangiectasia gene mutations in leukaemia and lymphoma. J Clin Pathol 2001; 54(7): 512-6.

Reference Link - Telatar M, Teraoka S, Wang Z, Chun HH, Liang T, Castellvi-Bel S et al. Ataxia-telangiectasia: identification and detection of founder-effect mutations in the ATM gene in ethnic populations. Am J Hum Genet 1998; 62(1): 86-97.

Reference Link - Athma P, Rappaport R, Swift M. Molecular genotyping shows that ataxia-telangiectasia heterozygotes are predisposed to breast cancer. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1996; 92(2): 130-4.

Reference Link - Thompson D, Duedal S, Kirner J, McGuffog L, Last J, Reiman A, Byrd P et al. Cancer risks and mortality in heterozygous ATM mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005; 97(11): 813-22.

Reference Link - Swift M. Genetic aspects of ataxia-telangiectasia. Immunodefic Rev 1990; 2(1): 67-81.

- Su Y, Swift M. Mortality rates among carriers of ataxia-telangiectasia mutant alleles. Ann Intern Med 2000; 133(10): 770-8.

- Prokopcova J, Kleibl Z, Banwell CM, Pohlreich P. The role of ATM in breast cancer development. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2007; 104(2): 121-8.

Reference Link - Gao Y, Hayes RB, Huang WY, Caporaso NE, Burdette L, Yeager M et al. DNA repair gene polymorphisms and tobacco smoking in the risk for colorectal adenomas. Carcinogenesis 2011; 32(6): 882-7.

Reference Link - Sanal O, Wei S, Foroud T, Malhotra U, Concannon P, Charmley P et al. Further mapping of an ataxia-telangiectasia locus to the chromosome 11q23 region. Am J Hum Genet 1990; 47(5): 860-866.

- Chen X, Yang L, Udar N, Liang T, Uhrhammer N, Xu S et al. CAND3: a ubiquitously expressed gene immediately adjacent and in opposite transcriptional orientation to the ATM gene at 11q23.1. Mamm Genome 1997; 8(2): 129-33.

Reference Link - Gatti RA, Berkel I, Boder E, Braedt G, Charmley P, Concannon P et al. Localization of an ataxia-telangiectasia gene to chromosome 11q22-23. Nature 1988; 336(6199): 577-80.

Reference Link - Uziel T, Savitsky K, Platzer M, Ziv Y, Helbitz T, Nehls M et al. Genomic Organization of the ATM gene. Genomics 1996; 33(2): 317-20.

Reference Link - Imai T, Yamauchi M, Seki N, Sugawara T, Saito T, Matsuda Y et al. Identification and characterization of a new gene physically linked to the ATM gene. Genome Res. 1996; 6(5): 439-47.

Reference Link - Imai T, Sugawara T, Nishiyama A, Shimada R, Ohki R, Seki N et al. The structure and organization of the human NPAT gene. Genomics 1997; 42(3): 388-92.

Reference Link - Byrd PJ, Cooper PR, Stankovic T, Kullar HS, Watts GD, Robinson PJ et al. A gene transcribed from the bidirectional ATM promoter coding for a Serine rich protein: amino acid sequence, structure and expression studies. Hum Mol Genet 1996; 5(11): 1785-91.

Reference Link - Gueven N, Keating K, Fukao T, Loeffler H, Kondo N, Rodemann HP et al. Site-directed mutagenesis of the ATM promoter: consequences for response to proliferation and ionizing radiation. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2003; 38(2): 157-67.

Reference Link - Gentilini F, Turba ME, Forni M, Cinotti S. Complete sequencing of full-length canine ataxia telangiectasia mutated mRNA and characterization of its putative promoter. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2009; 128(4): 437-40.

Reference Link - Platzer M, Rotman G, Bauer D, Uziel T, Savitsky K, Bar-Shira A, Gilad S, Shiloh Y, Rosenthal A. 1997. Ataxia-telangiectasia locus: sequence analysis of 184 kb of human genomic DNA containing the entire ATM gene. Genome Res. 7(6):592-605.

- Gueven N, Keating KE, Chen P, Fukao T, Khanna KK, Watters D et al. Epidermal growth factor sensitises cells to ionizing radiation by down-regulating protein mutated in ataxia-telangiectasia. J Biol Chem 2001; 276(12): 8884-91.

Reference Link - Hirai Y, Hayashi T, Kubo Y, Hoki Y, Arita I, Tatsumi K et al. X-irradiation induces up-regulation of ATM gene expression in wild-type lymphoblastoid cell lines, but not in their heterozygous or homozygous ataxia-telangiectasia counterparts. Jpn J Cancer Res 2001; 92(6): 710-7.

Reference Link - Khalil HS, Tummala H, Oluwaseun OA, Zhelev N. Novel insights of Ataxia Telangiectasia Mutated (ATM) regulation and its potential as a target for therapeutic intervention in cancer. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2011; 22(1): S115-S116.

Reference Link - Khalil HS, Tummala H, Hupp TR, Zhelev N. Pharmacological inhibition of ATM by KU55933 stimulates ATM transcription. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2012; 237: 622-34.

Reference Link - Savitsky K, Platzer M, Uziel T, Gilad S, Sartiel A, Rosenthal A et al. Ataxia-telangiectasia: structural diversity of untranslated sequences suggests complex post-transcriptional regulation of ATM gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res 1997; 25(9): 1678-84.

Reference Link - Gueven N, Fukao T, Luff J, Paterson C, Kay G, Kondo N et al. Regulation of the Atm promoter in vivo. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2006; 45(1): 61-71.

Reference Link - Fukao T, Kaneko H, Birrell G, Gatei M, Tashita H, Yoshida T et al. ATM is upregulated during the mitogenic response in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Blood 1999; 94(6):1998-2006

- Clyde RG, Craig AL, de Breed L, Bown JL, Forrester L, Vojtesek B et al. A novel ataxia-telangiectasia mutated autoregulatory feedback mechanism in murine embryonic stem cells. J R Soc Interface 2009; 6(41): 1167-77.

Reference Link - Chen G, Lee EYHP. The product of the ATM gene is a 370-kDa nuclear phosphoprotein. J Biol Chem 1996; 271(52): 33693-7.

Reference Link - Morgan SE, Lovly C, Pandita TK, Shiloh Y, Kastan MB. Fragments of ATM which have dominant-negative or complementing activity. Mol Cell Biol 1997; 17(4): 2020-9.

- Shafman T, Khanna KK, Kedar P, Spring K, Kozlov S, Yen T et al. Interaction between ATM protein and c-Abl in response to DNA damage. Nature 1997; 387(6632): 520-3.

Reference Link - Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB. DNA damage activates ATM through intermolecular autophosphorylation and dimer dissociation. Nature 2003; 421(6922): 499-506.

Reference Link - Kozlov SV, Graham ME, Peng C, Chen P, Robinson PJ, Lavin MF. Involvement of novel autophosphorylation sites in ATM activation. EMBO J 2006; 25(15): 3504-14.

Reference Link - Kozlov SV, Graham ME, Jakob B, Tobias F, Kijas AW, Tanuji M et al. Autophosphorylation and ATM activation: additional sites add to the complexity. J Biol Chem 2011; 286(11): 9107-19.

Reference Link - Matsuoka S, Ballif BA, Smogorzewska A, McDonald ER 3rd, Hurov KE, Luo J et al. ATM and ATR substrate analysis reveals extensive protein networks responsive to DNA damage. Science 2007; 316(5828): 1160-1166.

Reference Link - Oppermann FS, Gnad F, Olsen JV, Hornberger R, Greff Z, K?ri G et al. Large-scale proteomics analysis of the human kinome. Mol Cell Proteomics 2009; 8(7):1751-64.

- Daub H, Olsen JV, Bairlein M, Gnad F, Oppermann FS, K?rner R et al. Kinase-selective enrichment enables quantitative phosphoproteomics of the kinome across the cell cycle. Mol Cell 2008; 31(3): 438-48.

- Kurz EU, Lees-Miller SP. DNA damage-induced activation of ATM and ATM-dependent signaling pathways. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004; 3(8-9): 889-900.

Reference Link - Chaturvedi P, Eng WK, Zhu Y, Mattern MR, Mishra R, Hurle MR et al. Mammalian Chk2 is a downstream effector of the ATM-dependent DNA damage checkpoint pathway. Oncogene 1999; 18(28): 4047-54.

Reference Link - Barlow C, Liyanage M, Moens PB, Tarsounas M, Nagashima K, Brown K et al. ATM deficiency results in severe meiotic disruption as early as leptonema of prophase I. Development 1998; 125(20): 4007-17.

- Xu B, O'Donnell AH, Kim ST, Kastan MB. Phosphorylation of serine 1387 in BRCA1 is specifically required for the Atm-mediated S-phase checkpoint after ionizing irradiation. Cancer Res 2002; 62(16): 4588-91.

- Brown KD, Ziv Y, Sadanandan SN, Chessa L, Collins FS, Shiloh Y et al. The ataxia-telangiectasia gene product, a constitutively expressed nuclear protein that is not up-regulated following genome damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997; 94(5): 1840-5.

Reference Link - Watters D, Khanna KK, Beamish H, Birrell G, Spring K, Kedar P et al. Cellular localisation of the ataxia-telangiectasia (ATM) gene product and discrimination between mutated and normal forms. Oncogene 1997; 14(16): 1911-21

Reference Link - Fang ZM, Lee CS, Sarris M, Kearsley JH, Murrell D, Lavin MF et al. Rapid radiation-induction of ATM protein levels in situ. Pathology 2001; 33(1): 30-6.

- Banin S, Moyal L, Shieh S, Taya Y, Anderson CW, Chessa L et al. Enhanced phosphorylation of p53 by ATM in response to DNA damage. Science 1998; 281(5383): 1674-7.

Reference Link - Westphal CH, Rowan S, Schmaltz C, Elson A, Fisher DE, Leder P. ATM and p53 cooperate in apoptosis and suppression of tumorigenesis, but not in resistance to acute radiation toxicity. Nat Genet 1997; 16(4): 397-401.

Reference Link - Powers, J.T., Hong, S., Mayhew, C.N., Rogers, P.M., Knudsen, E.S., Johnson, D.G., E2F1 uses the ATM signaling pathway to induce p53 and Chk2 phosphorylation and apoptosis. Mol Cancer Res 2004; 2(4): 203-14.

- Gannon HS, Woda BA, Jones SN. ATM Phosphorylation of Mdm2 Ser394 Regulates the Amplitude and Duration of the DNA Damage Response in Mice. Cancer Cell 2012; 21(5): 668-79.

Reference Link - Xu Y, Baltimore D. Dual roles of ATM in the cellular response to radiation and in cell growth control. Genes Dev 1996; 10(19):2401-10.

Reference Link - Chong MJ, Murray MR, Gosink EC, Russell HR, Srinivasan A, Kapsetaki M, et al. Atm and Bax cooperate in ionizing radiation-induced apoptosis in the central nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000; 97(2): 889-94.

Reference Link - Carney JP, Maser RS, Olivares H, Davis EM, Le Beau M, Yates JR 3rd et al. The hMre11/hRad50 protein complex and Nijmegen breakage syndrome: linkage of double-strand break repair to the cellular DNA damage response. Cell 1998; 93(3): 477-86.

Reference Link - Burma S, Chen BP, Murphy M, Kurimasa A, Chen DJ. ATM phosphorylates histone H2AX in response to DNA double-strand breaks. J Biol Chem 2001; 276(45):42462-7.

Reference Link - Hopfner KP, Karcher A, Craig L, Woo TT, Carney JP, Tainer JA. Structural biochemistry and interaction architecture of the DNA double-strand break repair Mre11 nuclease and Rad50-ATPase. Cell 2001; 105(4): 473-85.

Reference Link - Wang Q, Zhang H, Fishel R, Greene MI. BRCA1 and cell signaling. Oncogene 2000; 19(53): 6152-8.

Reference Link - Sun Y, Xu Y, Roy K, Price BD. DNA damage-induced acetylation of lysine 3016 of ATM activates ATM kinase activity. Mol Cell Biol 2007; 27(24): 8502-9.

Reference Link - Matsuoka S, Rotman G, Ogawa A, Shiloh Y, Tamai K, Elledge SJ. Ataxia telangiectasia-mutated phosphorylates Chk2 in vivo and in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000; 97(19): 10389-94.

Reference Link - Gatei M, Sloper K, Sorensen C, Sylju?sen R, Falck J, Hobson K et al. Ataxia-telangiectasia-mutated (ATM) and NBS1-dependent phosphorylation of Chk1 on Ser-317 in response to ionizing radiation. J Biol Chem 2003; 278(17): 14806-11.

- Shieh SY, Ahn J, Tamai K, Taya Y, Prives C. The human homologs of checkpoint kinases Chk1 and Cds1 (Chk2) phosphorylate p53 at multiple DNA damage-inducible sites. Genes Dev 2000; 14(3): 289-300.

- Sahu RP, Batra S, Srivastava SK. Activation of ATM/Chk1 by curcumin causes cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human pancreatic cancer cells. Br J Cancer 2009; 100(9): 1425-33.

Reference Link - Stiewe T, P?tzer BM. Role of the p53-homologue p73 in E2F1-induced apoptosis. Nat Genet 2000; 26(4): 464-9.

Reference Link - Wang JY. Regulation of cell death by the Abl tyrosine kinase. Oncogene 2000 19(49): 5643-50.

Reference Link - Thompson LH, Schild D. Recombinational DNA repair and human disease. Mutat Res 2002; 509(1-2): 49-78.

Reference Link - Nouspikel TP, Hyka-Nouspikel N, Hanawalt PC. Transcription domain-associated repair in human cells. Mol Cell Biol 2006; 6(23):8722-30.

Reference Link - Chakarov S, Russev G. DNA repair and differentiation ? does getting older means getting wiser as well? Biotechnol Biotech Eq 2010; 24(2): 1804-6.

Reference Link - Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. Surfing the p53 network. Nature 2000; 408(6810): 307-10.

Reference Link - Smith J, Tho LM, Xu N, Gillespie DA. The ATM-Chk2 and ATR-Chk1 pathways in DNA damage signaling and cancer. Adv Cancer Res 2010; 108: 73-112.

Reference Link - Jung M, Dritschilo A. NF-kappa B signalling pathway as a target for human tumor radiosensitisation. Semin Radiat Oncol 2001; 11(4): 346-51.

Reference Link - Rogoff HA, Pickering MT, Frame FM, Debatis ME, Sanchez Y, Jones S, Kowalik TF. Apoptosis associated with deregulated E2F activity is dependent on E2F1 and Atm/Nbs1/Chk2. Mol Cell Biol 2004; 24(7): 2968-77.

Reference Link - Gajewski E, Gaur S, Akman SA, Matsumoto L, van Balgooy JN, Doroshow JH. Oxidative DNA base damage in MCF-10A breast epithelial cells at clinically achievable concentrations of doxorubicin. Biochem Pharmacol 2007; 73(12): 1947-56.

Reference Link - Hickson I, Zhao Y, Richardson CJ, Green SJ, Martin NM, Orr AI, Reaper PM, Jackson SP, Curtin NJ, Smith GC. Identification and characterization of a novel and specific inhibitor of the ataxia-telangiectasia mutated kinase ATM. Cancer Res 2004; 64(24): 9152-9.

Reference Link - Golding SE, Rosenberg E, Valerie N, Hussaini I, Frigerio M, Cockcroft XF, Chong WY, Hummersone M, Rigoreau L, Menear KA, O'Connor MJ, Povirk LF, van Meter T, Valerie K. Improved ATM kinase inhibitor KU-60019 radiosensitises glioma cells, compromises insulin, AKT and ERK prosurvival signaling, and inhibits migration and invasion. Mol Cancer Ther 2009; 8(10): 2894-902.

Reference Link - Rainey MD, Charlton ME, Stanton RV, Kastan MB. Transient inhibition of ATM kinase is sufficient to enhance cellular sensitivity to ionizing radiation. Cancer Res 2008; 68(18): 7466-74.

Reference Link - Peasland A, Wang LZ, Rowling E, Kyle S, Chen T, Hopkins A, Cliby WA, Sarkaria J, Beale G, Edmondson RJ, Curtin NJ. Identification and evaluation of a potent novel ATR inhibitor, NU6027, in breast and ovarian cancer cell lines. Br J Cancer 2011; 105(3): 372-81.

Reference Link - Alao JP, Sunnerhagen P. The ATM and ATR inhibitors CGK733 and caffeine suppress cyclin D1 levels and inhibit cell proliferation. Radiat Oncol 2009; 10;4: 51.

- Sarkaria JN, Busby EC, Tibbetts RS, Roos P, Taya Y, Karnitz LM, Abraham RT. Inhibition of ATM and ATR kinase activities by the radiosensitizing agent, caffeine. Cancer Res 1999; 59(17): 4375-82.

- Zhao Y, Thomas HD, Batey MA, Cowell IG, Richardson CJ, Griffin RJ, Calvert AH, Newell DR, Smith GC, Curtin NJ. Preclinical evaluation of a potent novel DNA-dependent protein kinase inhibitor NU7441. Cancer Res 2006; 66(10): 5354-62.

Reference Link - Vlahos CJ, Matter WF, Hui KY, Brown RF. A specific inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, 2-(4-morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one (LY294002). J Biol Chem 1994; 269(7): 5241-8.

- Sarkaria JN, Randal ST, Ericka CB, Amy PK, David EH, Robert TA. Inhibition of Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase Related Kinases by the Radiosensitizing Agent Wortmannin. Cancer Research 1998; 58(19): 4375-82.

- Postel-Vinay S, Vanhecke E, Olaussen KA, Lord CJ, Ashworth A, Soria JC. The potential of exploiting DNA-repair defects for optimizing lung cancer treatment. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2012; 9(3): 144-55.

Reference Link - Zabludoff SD, Deng C, Grondine MR, Sheehy AM, Ashwell S, Caleb BL, Green S, Haye HR, Horn CL, Janetka JW, Liu D, Mouchet E, Ready S, Rosenthal JL, Queva C, Schwartz GK, Taylor KJ, Tse AN, Walker GE, White AM. AZD7762, a novel checkpoint kinase inhibitor, drives checkpoint abrogation and potentiates DNA-targeted therapies. Mol Cancer Ther 2008; 7(9): 2955-66.

Reference Link - Blasina A, Hallin J, Chen E, Arango ME, Kraynov E, Register J, Grant S, Ninkovic S, Chen P, Nichols T, O'Connor P, Anderes K. Breaching the DNA damage checkpoint via PF-00477736, a novel small-molecule inhibitor of checkpoint kinase 1. Mol Cancer Ther 2008; 7(8): 2394-404.

Reference Link - Arienti KL, Brunmark A, Axe FU, McClure K, Lee A, Blevitt J, Neff DK, Huang L, Crawford S, Pandit CR, Karlsson L, Breitenbucher JG. Checkpoint kinase inhibitors: SAR and radioprotective properties of a series of 2-arylbenzimidazoles. J Med Chem 2005; 48(6): 1873-85.

Reference Link - Kawabe T. G2 checkpoint abrogators as anticancer drugs. Mol Cancer Ther 2004; 3(4): 513-9.

- Riesterer O, Matsumoto F, Wang L, Pickett J, Molkentine D, Giri U, Milas L, Raju U. A novel Chk inhibitor, XL-844, increases human cancer cell radiosensitivity through promotion of mitotic catastrophe. Invest New Drugs 2011; 29(3): 514-22.

Reference Link - McNeely SC, Burke TF, DurlandBusbice SS, Barnard DS, Marshall MS, Bence AK et al. LY2606368, a second generation Chk1 inhibitor, inhibits growth of ovarian carcinoma xenografts either as monotherapy or in combination with standard-of-care agents. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 2011; 10(11) A108.

- Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, Tutt A, Wu P, Mergui-Roelvink M et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med 2009; 361(2): 123-34.

Reference Link - Dolan ME, Stine L, Mitchell RB, Moschel RC, Pegg AE. Modulation of mammalian O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase in vivo by O6-benzylguanine and its effect on the sensitivity of a human glioma tumor to 1-(2-chloroethyl)-3-(4-methylcyclohexyl)-1-nitrosourea. Cancer Commun 1990; 2(11): 371-7.

- Plummer R, Jones C, Middleton M, Wilson R, Evans J, Olsen A et al. Phase I study of the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor, AG014699, in combination with temozolomide in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14(23): 7917-23.

Reference Link - te Poele RH, Okorokov AL, Jardine L, Cummings J, Joel SP. DNA damage is able to induce senescence in tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res 2002; 62(6): 1876-83.

- Crescenzi E, Palumbo G, de Boer J, Brady HJ. Ataxia telangiectasia mutated and p21CIP1 modulate cell survival of drug-induced senescent tumor cells: implications for chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14(6): 1877-87.

Reference Link - Guha C, Guha U, Tribius S, Alfieri A, Casper D, Chakravarty P et al. Antisense ATM gene therapy: a strategy to increase the radiosensitivity of human tumors. Gene Ther 2000; 7(10): 852-8.

Reference Link - Collis SJ, Swartz MJ, Nelson WG, DeWeese TL. Enhanced radiation and chemotherapy-mediated cell killing of human cancer cells by small inhibitory RNA silencing of DNA repair factors. Cancer Res 2003; 63(7): 1550-4.

- Neijenhuis S, Verwijs-Janssen M, van den Broek LJ, Begg AC, Vens C. Targeted radiosensitization of cells expressing truncated DNA polymerase {beta}. Cancer Res 2010; 70(21): 8706-14.

Reference Link - Truman JP, Gueven N, Lavin M, Leibel S, Kolesnick R, Fuks Z et al. Down-regulation of ATM protein sensitises human prostate cancer cells to radiation-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem 2005; 280(24): 23262-72.

Reference Link - Idowu M, Goltsov A, Khalil HS, Tummala H, Zhelev N, Bown J. Cancer research and personalised medicine: a new approach to modelling time-series data using analytical methods and Half systems. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2011; 22(S1): 59.

Reference Link