Introduction

Neutrophils and macrophages engulf not only microorganisms but also damaged tissue and degrade these materials in the phagolysosome [

The function of macrophages in wound healing has been well studied. Classically activated macrophages (M1 macrophages) mediate defense of the host from a

variety of bacteria, protozoa and viruses, and have roles in antitumor immunity. Alternatively activated macrophages (M2 macrophages) have

anti-inflammatory functions and regulate wound healing. 'Regulatory' macrophages can secrete large amounts of interleukin-10 (IL-10) in response to Fc

receptor-γ ligation [

We have recently shown that Gr1+CD11b+ cells increased in the spleen of dextran sulphate sodium (DSS)-treated mice during the recovery phase and splenectomy worsened the colitis

[

During infection, the innate immune system functions to kill microorganisms that induce tissue damage. Once immune cells clear the microorganisms, tissue regeneration occurs and damaged tissues are repaired. However, if the immune system fails to clear all the microorganisms such as hepatitis C virus, repeated stimulation by the virus will induce tissue destruction and finally organ failure. We hypothesize that although immune cells repair single damage, continuous stimulation of the immune system may induce chronic inflammation and induce tissue degeneration. Here we examined the function of neutrophils in wound healing by single or repeated stimulation of oxidative tissue damage by ROS-producing materials.

Results

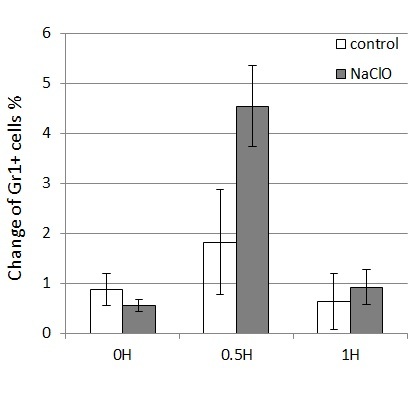

A single application of NaClO induces migration of neutrophils to a wound site

As it has been shown that ROS induces neutrophil migration to wound sites in zebrafish [

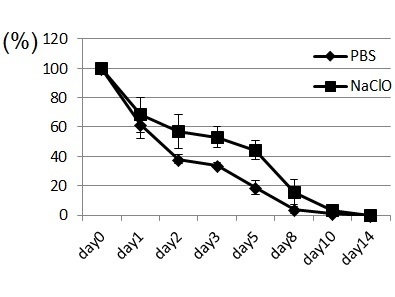

Repeated application of NaClO prolongs wound healing

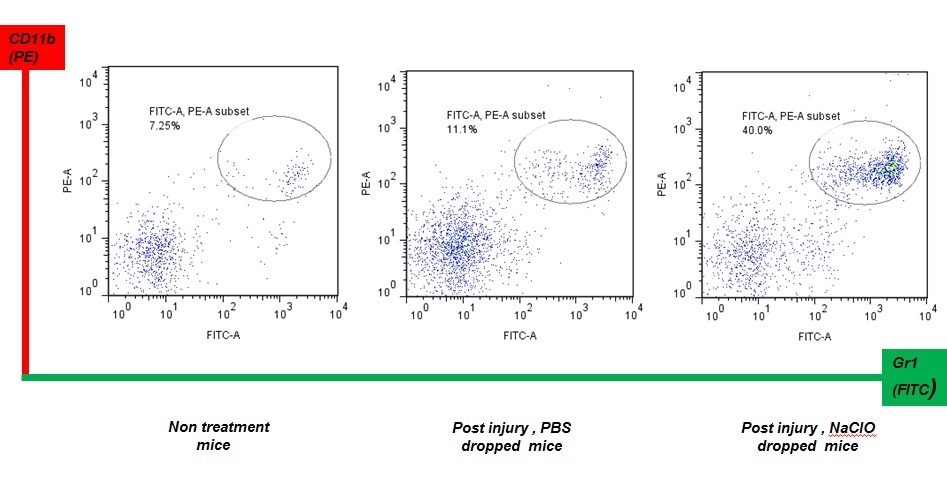

We thought that repeated exposure of ROS might affect wound healing. If wounds are repeatedly treated with NaClO, neutrophils must be continuously provided by an organ from which they originate. Spleen and bone marrow in mice have hematopoietic stem cells, which provide new neutrophils. GR-1+CD11b+ cells are a mixed population, containing precursors of neutrophils in addition to mature neutrophils. As shown in Fig. 2, application of NaClO for 5 days strongly damaged the skin tissue of mice and delayed wound healing. Upon examination of the spleens of mice that were subject to repeated application of NaClO, GR-1 +CD11b+ positive cells were shown to be up-regulated during the recovery phase of wounding (Fig. 3).

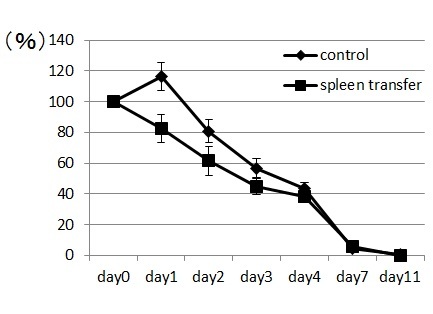

Transfer of GR-1+CD11b+ positive cells induces early recovery from wounding

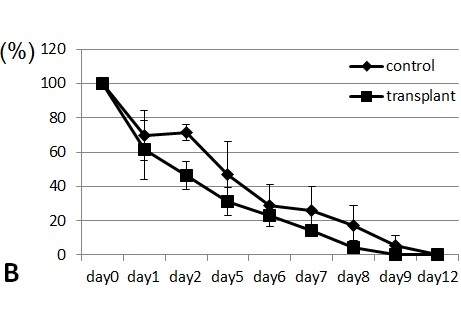

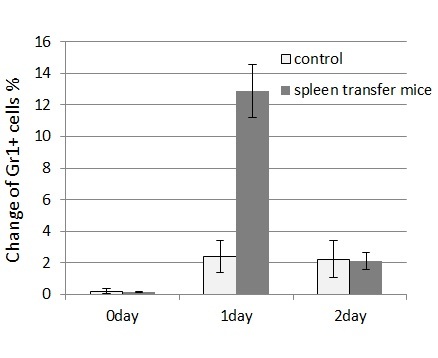

Spleen cells from wounded mice that had received 11-day treatments with NaClO were removed and transplanted intravenously to syngeneic ICR mice. The transplanted mice were subsequently wounded and recovery from the wounds was monitored. Mice that received the transplanted spleen cells from NaClO-administered mice recovered faster than mice that received the control spleen ( Figure 4). GR-1+CD11b+ -positive cells from the bone marrow of untreated ICR mice were FACS sorted, cytospinned, and stained by Gimsa. Many of the GR-1+CD11b+ cells were shown to be neutrophils, as indicated by their ring-shaped nucleus. Some of the cells were immature myeloid-lineage cells (Fig. 5A). The sorted GR-1+CD11b+ cells were injected into syngeneic ICR mice intravenously. Mice that received the transplanted GR-1+CD11b + cells recovered faster than the mice that received the control PBS. (Fig.5B). Then we examined the appearance of neutrophils at the wounded sites. We found that GR-1+ neutrophils appeared earlier and higher in the wounded tissues of the mice that received the spleen cells from NaClO - administered mice, than in the control mice (Fig.6).

Discussion

We have shown here that application of NaClO to wounded tissue induces neutrophil migration to the wound site. This migration was found to be transient

after a single application of NaClO. Thus, we applied NaClO for 5 days to wound sites to induce continuous neutrophil migration. Neutrophils produce

ROS, lytic enzymes and antimicrobial peptides, which facilitates the killing of microorganisms and clear damaged tissues [

Servettaz et al. developed the murine model of dermal sclerosis by repeated injection of ROS-inducing agents, including NaClO [

Materials and Methods

Mice

8-18 week-old ICR mice were originally purchased from SLC Japan and maintained at the Animal Research Facility at Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine under specific pathogen-free conditions and used according to institutional guidelines.

Excision wound preparation and macroscopic examination

Avertin (0.2ml per gram of body weight) was used as anesthesia during the wound generation and skin removal. After shaving and extensive cleaning with 70% ethanol, the dorsal skin was picked up at the midline and holes were punched through two layers of skin with a sterile disposable biopsy punch (diameter 3 mm; Kai Industries, Tokyo, Japan). At one side NaClO (available Cl 1-2.5%) was dropped and on the other side PBS was dropped as a control. This procedure generated two excisional full-thickness wounds on each side of the midline. The same procedure was repeated 3-5 times, generating 6-10 wounds on each animal. Each wound site was digitally photographed at the indicated time intervals, and wound areas were delineated using Excel software. Changes in wound areas were expressed as the proportion of the change in wound area relative to the initial wound area. In some experiments, wounds and their surrounding areas (including the scab and epithelial margins) were removed for further analysis using a sterile disposable biopsy punch with a diameter of 6 mm (Kai Industries) at the indicated time points.

FACS analysis and cell sorting

Wound tissue and spleen were gently clashed by rubber. Single cell suspensions were obtained by passing through stainless mesh and washed with PBS. Cells were treated with FITC-labeled anti-mouse Gr-1 or PE-labeled anti-mouse CD11b (BD Pharmingen). Cells were sorted with a FACS Aria (BD Biosciences) and data analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Tanaka for technical assistance with flow cytometry and N. Oiwa for secretarial work. This work was supported by the Ministry of Education, Science, Technology, Sports and Culture, Japan and the Global Centers of Excellence Program of Nagoya University.

References

- Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol 2005; 5(12): 953-64.

Reference Link - Geissmann F, Gordon S, Hume DA, Mowat AM, Randolph GJ. Unravelling mononuclear phagocyte heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol 2010; 10(6): 453-60.

Reference Link - Ricardo SD, van Goor H, Eddy AA. Macrophage diversity in renal injury and repair. J Clin Invest 2008; 118(11): 3522-30.

Reference Link - Wynn TA, Barron L. Macrophages: master regulators of inflammation and fibrosis. Semin Liver Dis 2010; 30(3): 245-57.

Reference Link - Murray PJ, Wynn TA. Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nat Rev Immunol 2011; 11(11): 723-37.

Reference Link - Singer AJ, Clark RA. Cutaneous wound healing. N Engl J Med 1999; 341(10): 738-46.

Reference Link - Martin P, Leibovich SJ. Inflammatory cells during wound repair: the good, the bad and the ugly. Trends Cell Biol 2005; 15(11): 599-607.

Reference Link - Chen GY, Nu?ez G. Sterile inflammation: sensing and reacting to damage. Nat Rev Immunol 2010; 10(12): 826-37.

Reference Link - Newton K, Dixit VM. Signaling in innate immunity and inflammation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2012; 4(3).

Reference Link - Rock KL, Latz E, Ontiveros F, Kono H. The sterile inflammatory response. Annu Rev Immunol 2010; 28: 321-42.

Reference Link - Sutterwala FS, Noel GJ, Clynes R, Mosser DM. Selective suppression of interleukin-12 induction after macrophage receptor ligation. J Exp Med 1997; 185(11): 1977-85.

Reference Link - Sutterwala FS, Noel GJ, Salgame P, Mosser DM. Reversal of proinflammatory responses by ligating the macrophage Fcgamma receptor type I. J Exp Med 1998; 188(1): 217-22.

Reference Link - Wynn TA. Fibrotic disease and the T(H)1/T(H)2 paradigm. Nat Rev Immunol 2004; 4(8): 583-94.

Reference Link - Xiao W, Hong H, Kawakami Y, Lowell CA, Kawakami T. Regulation of myeloproliferation and M2 macrophage programming in mice by Lyn/Hck, SHIP, and Stat5. J Clin Invest 2008; 118(3): 924-34.

- Simpson DM, Ross R. The neutrophilic leukocyte in wound repair a study with antineutrophil serum. J Clin Invest 1972; 51(8): 2009-23.

Reference Link - Leibovich SJ, Ross R. The role of the macrophage in wound repair. A study with hydrocortisone and antimacrophage serum. Am J Pathol 1975; 78(1): 71-100.

- Nishio N, Okawa Y, Sakurai H, Isobe K. Neutrophil depletion delays wound repair in aged mice. Age (Dordr) 2008; 30(1): 11-9.

Reference Link - Zhang R, Ito S, Nishio N, Cheng Z, Suzuki H, Isobe K. Up-regulation of Gr1+CD11b+ population in spleen of dextran sulfate sodium administered mice works to repair colitis. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets 2011; 10(1): 39-46.

Reference Link - Zhang R, Ito S, Nishio N, Cheng Z, Suzuki H, Isobe KI. Dextran sulphate sodium increases splenic Gr1(+)CD11b(+) cells which accelerate recovery from colitis following intravenous transplantation. Clin Exp Immunol 2011; 164(3): 417-27.

Reference Link - Niethammer P, Grabher C, Look AT, Mitchison TJ. A tissue-scale gradient of hydrogen peroxide mediates rapid wound detection in zebrafish. Nature 2009; 459(7249): 996-9.

Reference Link - Nathan C. Neutrophils and immunity: challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Immunol 2006; 6(3): 173-82.

Reference Link - Borregaard N. Neutrophils, from marrow to microbes. Immunity 2010; 33(5): 657-70.

Reference Link - Servettaz A, Goulvestre C, Kavian N, Nicco C, Guilpain P, Ch?reau C et al. Selective oxidation of DNA topoisomerase 1 induces systemic sclerosis in the mouse. J Immunol 2009; 182(9): 5855-64.

- Ishikawa H, Takeda K, Okamoto A, Matsuo S, Isobe K. Induction of autoimmunity in a bleomycin-induced murine model of experimental systemic sclerosis: an important role for CD4+ T cells. J Invest Dermatol 2009; 129(7): 1688-95.

Reference Link