Introduction

Neutrophils represent the largest population of circulating white blood cells, and form an essential component of the innate immune system, the primitive form of cellular immunity that is believed to have predated the development of T cells and B cells in evolution, and which remains the first line of defence in mammals. In outline, the presence of bacterial cell wall components in tissues activates macrophages, which respond by releasing inflammatory cytokines. Interleukin 8, in particular, attracts neutrophils to the site of infection [

Formation of ROS is thus an essential part of the elimination of bacterial infection by neutrophils [

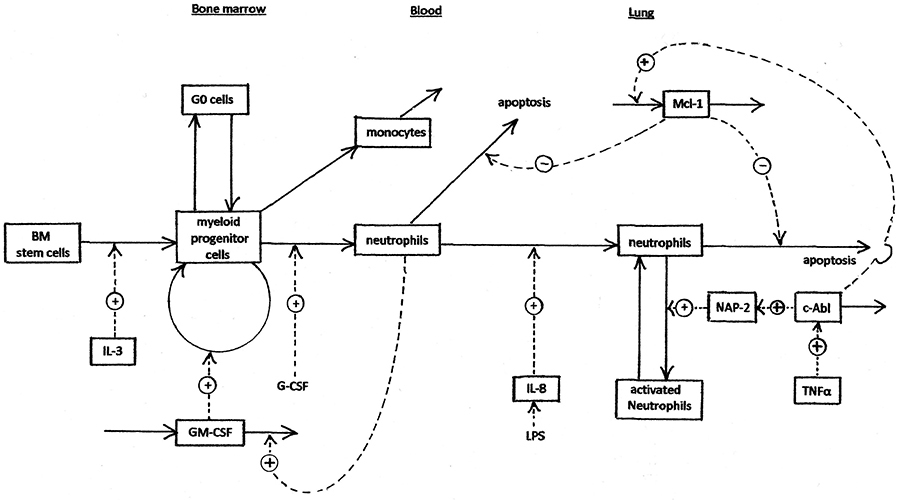

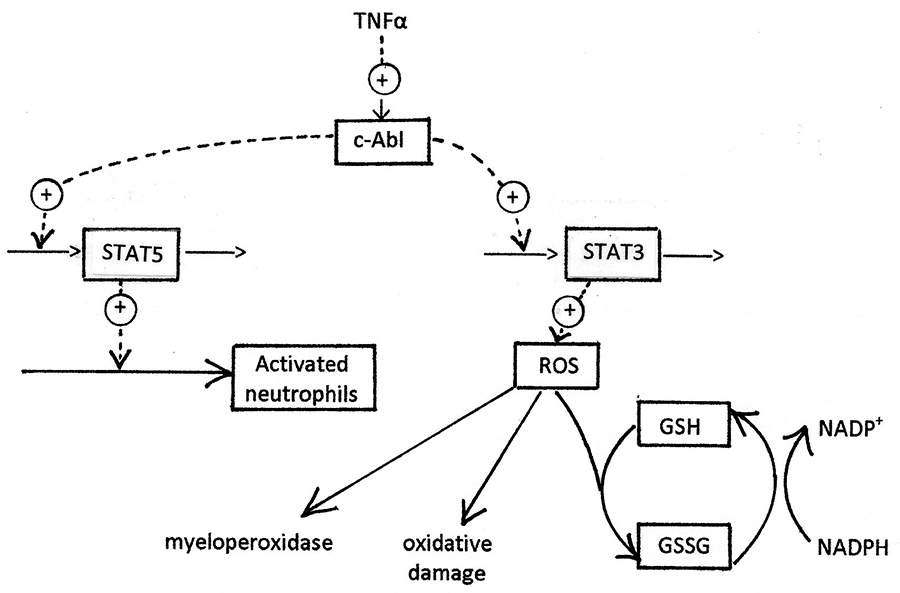

The process of neutrophil generation, trafficking, and activation is summarised in figure 1, which shows the activation of production of Mcl-1 (and thus inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis) by c-Abl. The other primary consequence of c-Abl activation, production of excessive ROS, is shown in more detail in figure 2. Several of the processes shown in figures 1 and 2 have been explored as targets for development of anti-inflammatory drugs. There has been particular interest in kinase inhibitors [

The kinetics of signalling pathways are complicated by multiple positive and negative feedback loops, cross-talk between the different pathways, action across multiple intracellular compartments, and oscillatory dynamics. Understanding these complex kinetics has been facilitated by constructing computer models of signalling networks [

Methods

Description of the myeloN Model

The scope of the model is shown in Figures 1 and 2. Bone marrow stem cells and myeloid progenitor cells are able to replicate. They remain localised in bone marrow. Neutrophils and monocytes do not replicate. The equations of the model are set out in the program listing (supplementary material). The system is basically a Bayesian prior belief model that is valid to the extent that it produces reasonable responses.

Control mechanisms of the model

- The proliferating population of myeloid progenitor cells has a kinetic reserve of G0 cells. These cells can be brought back into cycle in response to depletion of the total proliferating compartment, e.g. after myelosuppressive chemotherapy (37).

- GM-CSF is increased when the number of circulating neutrophils is low (e.g. after chemotherapy). The model treats this as binding of GM-CSF by circulating neutrophils (in which it has no effect), thus lowering the steady-state level of GM-CSF. This is a major homeostatic mechanism.

- Interleukin 8 is stimulated by lipopolysaccharide (LPS), e.g. after infection, resulting in increased trafficking of neutrophils from blood into tissues. Infection also causes increased TNFα.

- c-Abl is activated by TNFα resulting from infection or inflammation. c-Abl then phosphorylates STAT5 and causes neutrophil activation by up-regulation of Mcl-1 and Bcl-x. These proteins are inhibitors of apoptosis.

- Interferon-α phosphorylates and dimerises STAT5, which drives transcription of ICSBP, which represses transcription of anti-apoptotic proteins.

- c-Abl activates production of IL-3 and GM-CSF.

Sites of drug action

Nine of the rate processes are subject to inhibition by drugs. The drug effects that are modelled are: (1) DNA cross-linking, which inhibits cell proliferation (e.g. busulphan); (2) Inhibition of GM-CSF (e.g. MOR103); (3) Inhibitors of c-Abl tyrosine kinase (e.g. imatinib); (4) inhibition of CXCR1 and CXCR2 cytokine receptors (e.g. SB272844); (5) DNA synthesis inhibitors (e.g. cytarabine); (6) Inhibitors of Mcl-1 transcription (e.g. seliciclib); (7) TNFα antagonists (e.g. infliximab); (8) Induction of ICSB transcription (e.g. α-interferon); (9) Anti-oxidants (e.g. ascorbate). Currently, only constant concentrations of drugs and cytokines are modelled.

Modelling infection

Infection is treated as an instantaneous event occurring at zero time. LPS, a bacterial cell wall component, induces a range of cytokines. IL-3, IL-8 and TNFα are explicitly simulated by the model. G-CSF, which is produced by activated macrophages, is also modelled. IL-8 then triggers migration of neutrophils from plasma into the infected tissue, while TNFα activates c-Abl. c-Abl stimulates the release of ROS from the mitochondrial electron transport chain. Other ROS sources were not modelled, though they could be. Regardless of their source, ROS interact with myeloperoxidase to release hypochlorite, which is bactericidal. The model then assumes that bacteria are destroyed by ROS, and that this effect follows a Hill equation. The saturation function given by the Hill equation is interpreted as a fraction of the maximum antibacterial effect, expressed as log kill per hour:

bk = bkmax * ROSn / (Km + ROSn).

Then the bacterial count at time t + dt = bacteriat / (10bk*dt). LPS, IL8 and TNFα change in proportion with the bacterial count.

Modelling inflammation

Inflammation, specifically COPD, is modelled by assuming a constant level of TNFα, which results in permanent activation of c-Abl. Only cells in the tissue are affected, and no c-Abl activation is assumed in blood or bone marrow.

Programming

The model is implemented in the programming language R [

Parameter values are listed in the supplementary material. Parameter estimates are based upon literature data [

Results

To demonstrate that the model predicted reasonable values in the absence of infection, inflammation, or drugs, we first simulated the unperturbed steady-state. Using the default starting conditions, with no activation of c-Abl, the system was stable (see supplementary material). Output from selected simulations is shown in the main text, and all simulations are summarized in the supplementary material. The modelled circulating neutrophil count was about 4.6 million/ml blood, and the steady-state count of tissue-infiltrating neutrophils was 75,000/gm tissue. Only 0.1% of these were activated in the absence of c-Abl stimulation. The calculated mean residence time of neutrophils in plasma was 4.7 days. A low steady state level of ROS was well within the capacity of neutrophil glutathione peroxidase to remove [

Interleukin 8 (IL-8) is produced by tissue macrophages, which are activated in the presence of bacterial or fungal infection, or inflammation. In the absence of infection or immune stimulation, tissue levels of IL-8 are very low. Simulation 2 modelled the effect of continuous exposure to a high concentration (50 nM) of IL-8. This treatment resulted in an increase in tissue neutrophils of about 2.6-fold, peaking at about 22 hours. An increase in activated tissue neutrophils was also predicted, of about 2.4-fold, peaking at 36 hr. There was a marked decline in the blood neutrophil count, correlating with the migration of these cells into tissues. The decreased blood neutrophil count triggered an increased proliferation of progenitor cells, which in turn began to restore the blood neutrophil count. ROS increased by about 2-fold, reflecting the increase in activated tissue neutrophils.

After treatment for 9 days with a maximum tolerated concentration of the interleukin 8 antagonist, SB272844, tissue neutrophils reached a nadir of 11% of the normal value. Circulating neutrophils increased (simulation 3). The level of ROS production decreased to about 50% control. These predictions are consistent with the IL-8 antagonist’s mechanism of inhibiting trafficking of neutrophils from blood into tissues.

A subsequent study (simulation 4) modelled the effect of IL-8 (50 nM) in presence of its antagonist, SB272844 (5 μM). As seen by comparing simulation 4 with simulation 3, the increase in tissue neutrophils caused by IL-8 was completely prevented. No increase in activated neutrophils was seen, in contrast to the 2.4-fold increase predicted in absence of SB272844. The increase in ROS driven by IL-8 was also completely blocked.

MOR103 is a monoclonal antibody that binds to GM-CSF and thus prevents its interaction with the GM-CSF receptor [

Simulation 6 examined the effect of increasing G-CSF to 5-fold the normal level. Over the first few days of treatment the model predicted an 11% increase in circulating neutrophils, coupled with a 46% decrease in myeloid progenitor cells. This relatively muted response presumably reflects the strong homeostatic regulation of circulating neutrophils, which cause feedback inhibition of the proliferation of progenitor cells [

In simulation 8, a bacterial infection (106 cells/gm tissue) is assumed to result in the presence of lipo-polysaccharide (LPS) in tissues. This activates macrophages, which release TNFα, and activation of c-Abl results. This causes a strong antibacterial response. By ten days, 99.9%+ (5.9 logs) of the bacteria have been eliminated, and the ROS level (which peaks at 84 h) is returning to normal. Following an initial dip in circulating neutrophils, as they migrate into the infected tissues, a moderate leucocytosis is seen, with circulating neutrophils peaking at 255% normal at 184 h.

The antibacterial response was dependent on the size of the bacterial challenge. Simulation 9 shows a bacterial challenge of 105 cells/gm tissue. By 10 days, the bacteria were completely eliminated. ROS peaked at 6.0x control at 60 h. Circulating neutrophils increased 21%, peaking at 240 h. After a very large bacterial challenge of 107 cells/gm tissue (simulation 10), ROS reached levels almost 50x baseline. Bacterial kill was about 6 logs, and circulating neutrophils peaked at 6.5-fold control, at 230 h. At these high levels of ROS accumulation, the redox buffer system of the cell is saturated, and significant amounts of oxidised glutathione appear.

In bacterial infection, the activation of c-Abl is driven, indirectly, by bacterial cell wall LPS. As the infection is eliminated, production of ROS tapers off. The antibacterial response is self-limited, so that oxidative damage to host tissues is minimal. The situation is different in inflammatory disease, where inflammatory cytokines, including TNFα, are produced continually, so that c-Abl is permanently activated. We modelled this situation by setting TNFα to a constant level of 5 nM (simulation 11). This resulted in c-Abl activation (0 – 6.34 in 48 h), activation of tissue neutrophils (5.6-fold in 48 h), Mcl-1 (7.1-fold), and ROS (3.8-fold, and still rising at 48 h). ROS production eventually levelled off at more than 50-fold the baseline value, a level likely to cause significant tissue damage. Circulating neutrophils increased moderately (40% at 48 h), and tissue neutrophils increased 61%, presumably because of decreased apoptosis. This situation may be regarded as a first approximation model of COPD, for the purposes of in silico drug screening.

If the primary cause of neutrophil activation in COPD is TNFα, one way to prevent c-Abl activation may be to treat with the anti-TNF antibody, infliximab. Simulation 12 summarises the result of simultaneous administration of TNFα and infliximab. Infliximab (5 nM) inhibited the response to TNFα, decreasing the effect on neutrophil activation by 81% at 48 h, the effect on ROS by 75%, and the effect on Mcl-1 by 83%.

There have been several studies of the effects of antioxidants, including ascorbate, on COPD, with some preliminary, but encouraging, results on biomarkers of oxidative stress [

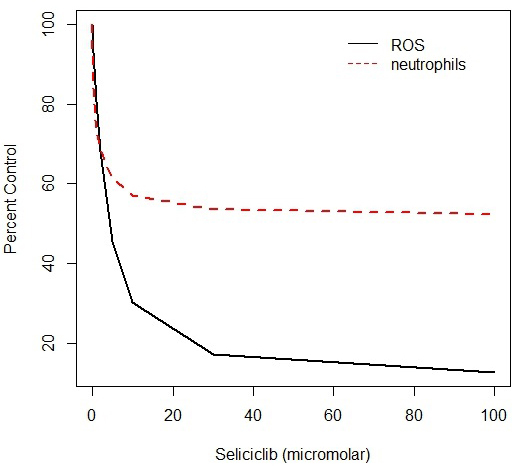

Because of evidence that the primary factor involved in neutrophil activation is the anti-apoptotic protein Mcl-1 [

Chronic myeloid leukaemia, CML, is a form of leukaemia in which a t(9:22) chromosomal translocation produces a fusion protein in which a c-Abl domain is fused to the protein product of the Bcr gene, and as a result the Abl domain is constitutively activated [

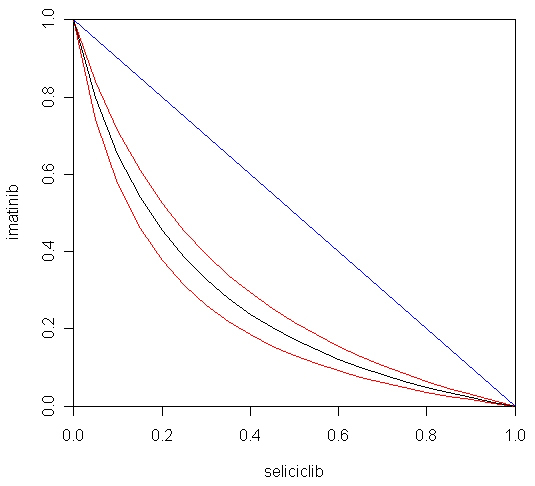

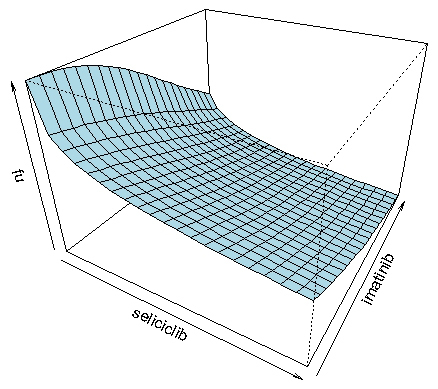

The fact that both imatinib and seliciclib were predicted to have strong activity against COPD, and by different mechanisms, suggested that it would be interesting to predict the efficacy of combinations of the two agents. The myeloN model was used to simulate effects of combinations of imatinib (at concentrations ranging from 10 – 120 nM) and seliciclib (0.3 – 70 μM). Results were analysed by fitting the three-dimensional dose-response surface to the equation of Greco et al. [

Figure 5 shows the drug interaction as a 3-dimensional response surface. This form of data presentation has the advantage that it covers the entire range of concentrations for both drugs. The complex shape of this plot reflects the fact that the slope of the Hill function for imatinib is much steeper than for seliciclib, creating an asymmetry in the shape of the surface. The R programming language, which was used to plot this figure, makes it possible to rotate the diagram on a computer screen, giving a better impression of the details of the response surface.

Another popular method of depicting drug interaction data is the median effect plot of Chou and Talalay [

![Figure 6. Combination index values for the imatinib + seliciclib combination. Predicted values of ROS calculated by the myeloN program were analysed by the method of Chou and Talalay [32]. Figure 6](https://biodiscovery.pensoft.net/showimg/oo_85801.jpg)

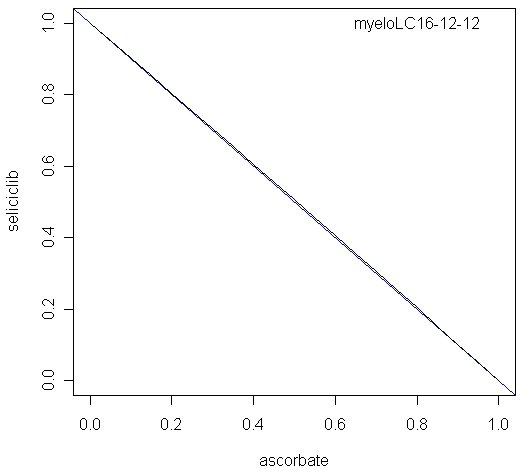

The combination of seliciclib and ascorbate was also modelled, using inhibition of ROS as endpoint. The calculated alpha parameter was -0.023, not significantly different from zero, indicating an additive interaction. The isobol plot for this combination is shown in Figure 7.

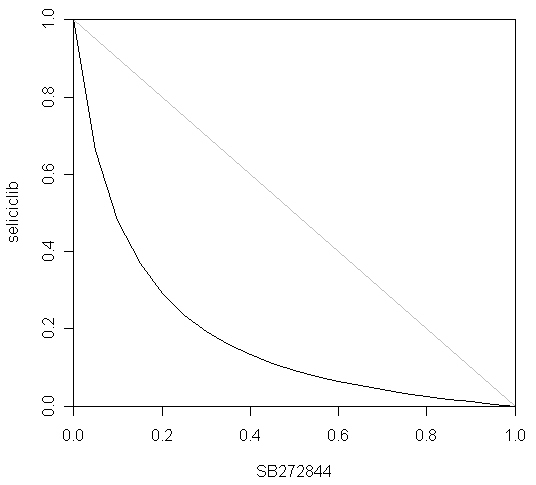

Finally, the myeloN program was used to model the interaction between seliciclib and SB272844. The rationale for this combination was that seliciclib triggers apoptosis of activated neutrophils, whereas SB272844 blocks trafficking of circulating neutrophils into tissues. Simulation 19 shows the effect of 1.34 μM seliciclib. Based upon the value of ROS at 480 h, the degree of inhibition is 50.0%, i.e. the fraction unaffected (fu) = 0.5.

Simulation 20 shows the effect of 2.43 μM SB272844. Over 480 h, this treatment reduces leakage of ROS by 50%, i.e. fu = 0.5. Simulation 21 shows the combined effect of 1.34 μM seliciclib plus 2.43 μM SB272844. ROS leakage is inhibited by 87.6% by 480 h, i.e. fu = 0.124. If the two drugs act independently, as defined by Bliss [

Discussion

The myeloN model captures the key qualitative features of neutrophil trafficking and activation, and of the response of these processes to infection and inflammation. cAbl appears to act as the primary control point for neutrophil activation, and in turn, through its effect on STAT transcription factors, activates multiple pathways. We have chosen to describe two of these in detail: the STAT5-mediated up-regulation of Mcl-1, which turns the normally transient tissue neutrophils into a much more long-lived cell population. Secondly, our model describes ROS production following neutrophil activation. This effect is driven by STAT3. Such ROS can arise from mitochondria, peroxisomes, or NADPH oxidase in the plasma membrane. In this paper we let mitochondrial ROS represent all three possible sources. ROS mediate the primary bactericidal function of neutrophils, but if they persist too long, they can cause serious oxidative damage to normal tissues. This tissue damage is a primary cause of morbidity in COPD and other inflammatory diseases.

A gatekeeper role of c-Abl is supported by the fact that its permanent activation results in malignant transformation. The Abelson murine leukaemia virus transforms murine lymphoblasts by expressing a constitutively activated form of the gene, v-Abl [

The aetiology of COPD is complex, but there is general agreement that production of inflammatory cytokines, stimulated by inhaled irritants such as tobacco smoke, is the primary cause. The tissue injury caused by COPD is attributable to oxidative damage, and it has been suggested that ROS present in tobacco smoke, as well as ROS produced by activated neutrophils, are responsible. ROS are equally harmful, regardless of their source, and it is likely that anti-oxidants may be beneficial whatever the source of the ROS. However, abnormally high ROS production persists long after cessation of smoking, and in such cases, at least, the primary source must be internal rather than external. Our computational model of COPD assumes that c-Abl is chronically activated, and this single factor is predicted to lead to all the other consequences: abnormally high numbers of tissue neutrophils, persistent activation of tissue neutrophils, elevated production of the anti-apoptotic protein Mcl-1, inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis, very high levels of ROS, represented here by electron leakage from the mitochondrial ETC, and resulting tissue injury.

The branched signalling pathway downstream from Bcr-Abl has interesting implications for the treatment of COPD. Since the damage to lung tissue in this disease is caused by ROS, it is reasonable to expect that antioxidants should have activity in this disease, and indeed the model predicts that this will be the case. However, the antioxidant effect, though providing symptomatic relief, does not address the causes of the problem, the continued activation of tissue neutrophils. Imatinib and seliciclib do cause depletion of activated tissue neutrophils, and the model predicts that they will be effective treatments for COPD. However, their effect is somewhat delayed, as the reactivation of apoptosis takes a few days to deplete the activated neutrophil population. Perhaps a combination of the two approaches will be superior to either used separately. The model suggests that the combined effects of ascorbate and seliciclib should be additive. Interestingly, the most striking synergy was predicted to result from the simultaneous triggering of tissue neutrophil apoptosis with seliciclib, and prevention of neutrophil trafficking from plasma into lung tissue, with SB272844.

The myeloN model thus provides a tool for rapid prediction of effective sites for drug intervention in COPD and other neutrophil-driven inflammatory conditions. Of course its predictions must be subjected to experimental verification, but the ability to explore a large number of possibilities in silico makes it possible to prioritise scarce experimental resources for those targets and drugs most likely to be successful. This is particularly the case for devising effective combination protocols. This is an inherently combinatorial problem, especially when multiple drugs, multiple dose levels, sequence-dependent effects and varying degrees of drug selectivity are involved. Based upon the nine sites for inhibition included in the myeloN model, there are (9 x 8)/2! = 36 mechanistically distinct binary inhibitor combinations. Of these, we have so far only explored three, of which one was predicted to be moderately synergistic, one additive, and one highly synergistic. In future studies we plan to explore the remaining 33 binary combinations and the (9 x 8 x 7)/3! = 84 possible three-drug combinations.

In some therapeutic areas, such as oncology [

The myeloN model, in its present form, is a PD model: it relates drug concentrations to a PD effect. As such, it can model the effect of constant drug concentrations, as in in vitro experiments. To describe in vivo drug effects, it will be necessary to combine the myeloN model with a pharmacokinetic (PK) model that describes how the drug distributes within the body, and how its concentration changes with time. When validated against in vivo experimental data, including biomarker measurements, and combined with human PK data, these PK/PD models have the potential to be used for in silico clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

TR was supported by NCI ICBP NO 5U54CA149233-029689 and by 1RO1CA138858.

References

- Baggiolini M, Clark-Lewis I. Interleukin 8, a chemotactic and inflammatory cytokine. FEBS Lett 1992; 307: 97-101.

Reference Link - Utsumi T, Klostergaard J, Akimaru K, Edashige K, Sato EF, Utsumi K. Modulation of TNF-alpha priming and stimulation-dependent superoxide generation in human neutrophils by protein kinase inhibitors. Arch Biochem Biophys 1992; 294: 271-278.

Reference Link - Schlatterer SD, Acker CM, Davies P. c-Abl in neurodegenerative disease. J Mol Neurosci 2011; 45: 445-452.

Reference Link - Nam S, Williams A, Vultur A, List A, Bhalla K, Smith D, Lee FY, Jove R. Dasatinib (BMS-354825) inhibits Stat5 signaling associated with apoptosis in chronic myelogenous leukemia cells. Mol Cancer Ther 2007; 6: 1400-1405.

Reference Link - Hancock JT. Cell Signalling (Third edition), p. 130. Oxford University Press 2010.

- Kirchner T, Möller S, Klinger M, Solbach W, Laskay T, Behnen M. The impact of various reactive oxygen species on the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. Mediators of Inflammation 2012; doi:10.1155/2012/849136.

Reference Link - MacNee W. Oxidants/antioxidants and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: pathogenesis to therapy. Novartis Found Symp 2001; 234: 169-185.

Reference Link - Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MT, Mazur M, Telser J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2007; 39: 44-84.

Reference Link - Reddy SP. The antioxidant response element and oxidative stress modifiers in airway diseases. Curr Mol Med 2008; 8: 376-383.

Reference Link - Christóvão C, Cristóvão C. Evaluation of the oxidant and antioxidant balance in the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Rev Port Pneumol 2013; 19(2): 70-75

- Adcock IM, Caramori G. Kinase targets and inhibitors for the treatment of airway inflammatory diseases: the next generation of drugs for severe asthma and COPD? Biodrugs 2004; 18: 167-180.

Reference Link - Rahman I, MacNee W. Antioxidant pharmacological therapies for COPD. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2012; 12: 256-265.

Reference Link - Rossi AG, Sawatsky DA, Walker A Ward C, Sheldrake TA, Riley NA et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors enhance the resolution of inflammation by promoting inflammatory cell apoptosis. Nat Med 2006; 12: 1056-1064.

Reference Link - Milot E, Filep JG. Regulation of neutrophil survival/apoptosis by Mcl-1. The Scientific World Journal 2011; 11: 1948-1962.

Reference Link - Leitch AE, Riley NA, Sheldrake TA, Festa M, Fox S, Duffin, R et al. The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor R-roscovitine down-regulates Mcl-1 to override pro-inflammatory signalling and drive neutrophil apoptosis. Eur J Immunol 2010; 40: 1127-1138.

Reference Link - Jackson RC, Barnett AL, McClue SJ, Green SR. Seliciclib, a cell-cycle modulator that acts through the inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases. Expert Opin Drug Discov 2008; 3: 131-143.

Reference Link - MacCallum DE, Melville J, Frame S Watt K, Anderson S, Gianella-Borradori A et al. Seliciclib (CYC202, R-roscovitine) induces cell death in multiple myeloma cells by inhibition of RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription and down-regulation of Mcl-1. Cancer Res 2005; 65: 5399-5407.

- Gilbert D, Fuss H, Gu X, Orton R, Robinson S, Vyshemirsky V et al. Computational methodologies for modelling, analysis and simulation of signalling networks. Brief Bioinform 2006; 7(4): 339-353.

Reference Link - Terry AJ, Chaplain MAJ. Spatio-temporal modelling of the NF-κB intracellular signalling pathway: The roles of diffusion, active transport, and cell geometry. J Theor Biol 2011; 290: 7-26.

Reference Link - Rubinow SI, Lebowitz JL. A mathematical model of neutrophil production and control in normal man. J Math Biol 1975; 1: 187-225.

Reference Link - Zhuge C, Lei J, Mackey MC. Neutrophil dynamics in response to chemotherapy and G-CSF. J Theor Biol 2012; 293: 111-120.

Reference Link - Brooks G, Provencher G, Lei J, Mackey MC. Neutrophil dynamics after chemotherapy and G-CSF: the role of pharmacokinetics in shaping the response. J Theor Biol 2012; 315: 97-109

Reference Link - Scholz M, Schirm S, Wetzler M, Engel C, Loeffler M. Pharmacokinetic and –dynamic modelling of G-CSF derivatives in humans. Theor Biol Med Model 2012; 9: 32-60.

Reference Link - Harrap KR, Jackson RC. Some biochemical aspects of leukaemias. Leukocyte glutathione metabolism in chronic granulocytic leukaemia. Eur J Cancer 1969; 5: 61-67.

Reference Link - www.morphosys.com/pipeline

- Shtivelman E, Lifshitz B, Gale RP, Canaani E. Fused transcript of abl and bcr genes in chronic myelogenous leukaemia. Nature 1985; 315: 550-554.

Reference Link - Carella AM, Daley GQ, Eaves CJ,Goldman JM, Rudier H. Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia: Biology and Treatment. London: Martin Dunitz (2001).

- Cortes J, Deinger M. Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. New York: Informa, 2007.

- Druker BJ, Talpaz M, Resta DJ, Peng B, Buchdunger E, Ford JM et al. Efficacy and safety of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 1031-1037.

Reference Link - Deininger M, Buchdunger E, Druker BJ. The development of imatinib as a therapeutic agent for CML. Blood 2005; 105: 2640-2653.

Reference Link - Greco WR, Park HS, Rustum YM. Application of a new approach for the quantitation of drug synergism to the combination of cis-diamminedichloroplatinum and 1-β-D-arabinofuranosylcytosine. Cancer Res 1990; 50: 5318-5327.

- Chou TC, Talalay P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv Enzyme Reg 1984; 22: 27-55.

Reference Link - Greco WR, Bravo G, Parsons JC. The search for synergy: a critical review from a response surface perspective. Pharmacol Rev 1995; 47: 331-385.

- Goff SP. The Abelson murine leukemia virus oncogene. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1985; 179: 403-412.

- Jackson RC. Pharmacodynamic modelling of biomarker data in oncology. ISRN Pharmacology 2012; 2012: 590626. Doi:10.5402/2012/590626.

- Chan JR, Vuillaume G, Bever C, Lebrun S, LietzM, Steffen Y et al. The apoe-/- mouse PhysioLab® platform: a validated physiologically-based mathematical model of atherosclerotic plaque progression in the apoe-/- mouse. Biodiscovery 2012; 3:2.

Reference Link - Jackson RC. The Theoretical Foundations of Cancer Chemotherapy Introduced by Computer Models. New York, Academic Press, 1992.

- Venables WN, Smith DM. An Introduction to R. Bristol: Network Theory Ltd, 2005.